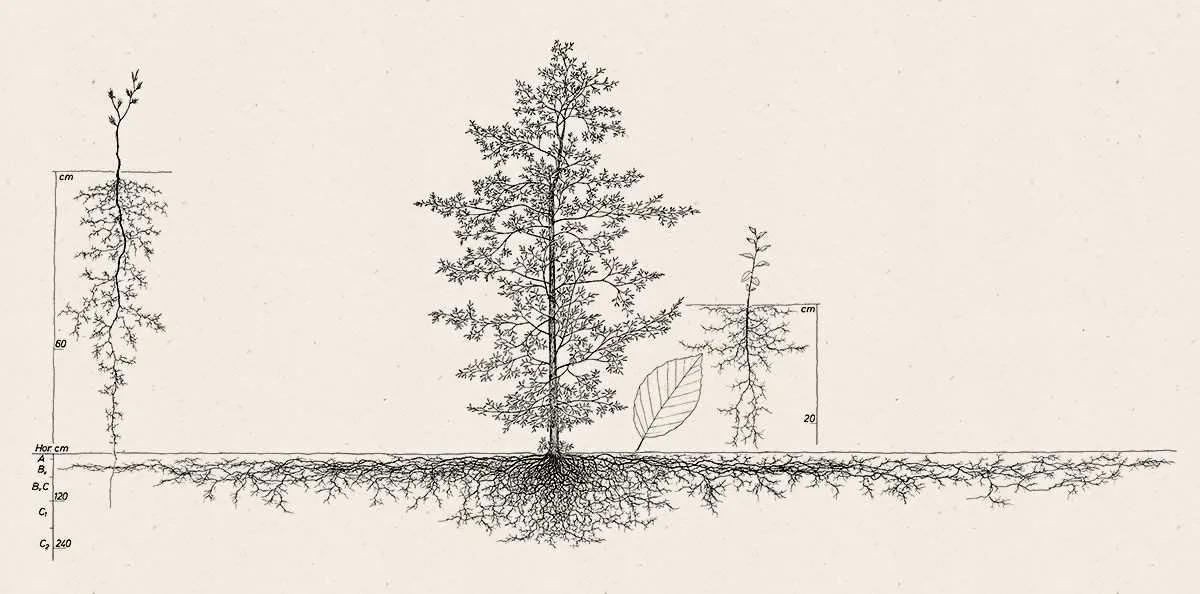

To fully grasp the subterranean architecture of an oak, it is crucial to recognize the complex interplay of various components beneath the surface. Focus on the extensive lateral extensions, which serve as anchors, absorbing nutrients and providing stability. These elements are complemented by vertical shafts that reach deeper soil layers, ensuring moisture retention during dry periods.

Notice how the network forms a dense, fibrous mesh, allowing for an effective exchange of water and minerals. The growth patterns of this structure play a significant role in how the organism adapts to its environment, particularly in nutrient-poor soils or areas with fluctuating water availability.

Key aspects include the diversity in diameter across the various extensions, which directly impacts the organism’s ability to access resources at varying depths. This can be observed in its ability to thrive in both compacted and loose soils.

For better insight, it’s recommended to examine this structure through both cross-sectional and lateral perspectives, as this reveals the true depth and breadth of its reach within the soil. By doing so, one can appreciate the efficiency of this intricate design in sustaining a robust, long-lived organism.

Understanding the Underground Network of an Oak

For optimal growth, focus on understanding the below-ground network of the plant, which is essential for water and nutrient absorption. These elements thrive in the extensive network, which can span several meters in depth and width.

- Taproot: The primary anchor that grows deep into the soil, providing stability and support.

- Lateral branches: These spread horizontally from the main shaft, reaching far and wide to gather moisture and nutrients.

- Fibrous strands: Fine, hair-like structures that permeate the soil and increase surface area for better absorption.

The spread of this underground network allows it to absorb water from a vast volume of soil, providing the necessary nutrients. Its robustness can be a factor in ensuring survival through dry spells and soil erosion. A well-established underground mass can prevent the plant from being uprooted in high winds or extreme weather conditions.

In mature examples, the horizontal reach of these structures can extend well beyond the canopy’s width, making it critical to assess the space around them when planting or planning surrounding land use. Avoid compacting the soil around the spread to ensure the network remains unhindered.

- Monitoring moisture: Ensure that the surrounding soil remains moist during the early stages of growth to facilitate deep penetration of the primary anchor.

- Soil aeration: Regular aeration improves the oxygen levels in the earth, supporting healthy development.

- Protection from disturbances: Avoid digging or disturbing the soil around the perimeter, as it can damage these vital extensions.

Understanding the Depth and Spread of Oak Roots

Maximizing Growth Potential: The underground network of an oak’s foundation typically extends far beyond the visible part of the plant. While the taproot initially grows deep, the majority of the lateral growth spreads in a radius up to 3 times the height of the mature plant. This horizontal spread is crucial for stability and nutrient uptake.

Growth Depth: In ideal conditions, the vertical growth of the central anchor can reach depths of 10 to 20 feet, depending on soil quality. However, it’s important to note that in compacted or poor soils, this depth may be restricted, leading to less robust development. Deeper penetrations occur in looser, well-drained soils.

Spread Considerations: Lateral extension plays a significant role in water and nutrient absorption. The majority of branching occurs within the top 18 inches of soil, maximizing access to surface moisture and organic matter. In dense, clay-rich soils, lateral expansion tends to be more restricted, while in sandy soils, roots can spread wider and deeper.

Impact of Environment: These factors influence both the depth and spread: moisture levels, soil type, and the surrounding plant life. In dry conditions, roots tend to grow deeper, seeking water reserves. Conversely, in moist conditions, they expand horizontally to cover a larger area for optimal resource collection.

Impact of Soil Type on Oak Tree Root Growth

For optimal growth, well-drained, loamy soil is ideal, as it supports deep penetration and development of underground structures. Sandy soils, while well-draining, can cause instability due to low nutrient retention, leading to shallow growth. On the other hand, heavy clay soils tend to retain excess moisture, restricting aeration and promoting root rot if drainage isn’t managed. The pH level of the soil is also critical; slightly acidic to neutral conditions (pH 6 to 7) promote healthier root expansion and nutrient uptake. Alkaline soils, however, can limit access to essential minerals, stunting growth. Regular soil testing and appropriate amendments ensure that the conditions remain favorable for underground development.

Soil texture affects the direction and depth of growth as well. In compacted or dense soils, roots tend to spread laterally near the surface rather than growing deeper. To avoid this, it’s important to loosen the soil or choose a planting site where compaction is minimal. Adding organic matter can enhance soil structure and facilitate better penetration. Additionally, soils rich in nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contribute significantly to stronger and healthier underground networks, allowing for better anchorage and resilience to environmental stress.

Monitoring and adjusting soil conditions based on these factors can significantly improve the development and longevity of the root network, ensuring long-term growth and stability.

How Oak Root Systems Affect Surrounding Plants and Structures

The underground network of an oak’s foundation can significantly impact nearby vegetation and buildings. The expansive horizontal growth of the foundational structure competes for water and nutrients, often leaving smaller plants with insufficient resources, leading to stunted growth or even death. This phenomenon is especially prominent when the root mass extends widely, often beyond the drip line, affecting a large area.

When it comes to structures, the invasive nature of these underground components can cause damage to foundations, driveways, and pipes. Roots can infiltrate cracks in concrete, widening them over time and leading to costly repairs. It’s crucial to manage the proximity of these growths to any infrastructure, ensuring that they are not positioned too close to vulnerable surfaces.

For gardeners or landscapers, it’s advised to plant other species with shallow or less aggressive underground growth patterns far from such extensive underground networks. This minimizes competition and the risk of structural damage. In urban areas, regular monitoring for potential root intrusions into sewer systems and paved surfaces is important for maintaining both plant health and infrastructure integrity.